HOME | REVIEWS: A-Z | FURTHER READING | NEWS | ABOUT

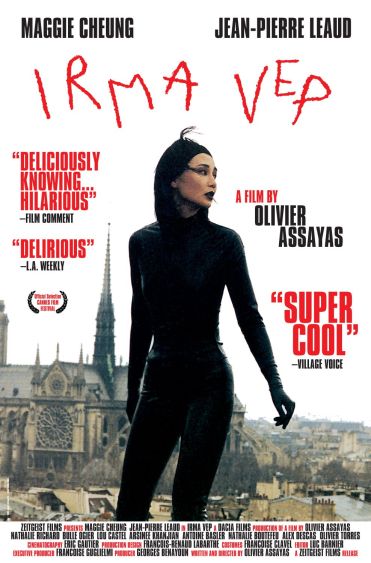

Irma Vep

1996 / Colour / 99 m. / France

Starring: Maggie Cheung, Jean-Pierre Leaud, Nathalie Richard, Antoine Basler, Nathalie Boutefeu, Alex Descas, Dominique Faysse, Bernard Nissile, Olivier Torres, Lou Castel

Cinematography: Eric Gautier

Art Director: Francois-Renaud Labarthe

Film Editor: Luc Barnier

Original Music: Philippe Richard

Produced by: Georges Benayoun

Written and Directed by: Olivier Assayas

Reviewed by Lee Broughton

Synopsis:

Aging film director Rene Vidal (Jean-Pierre Leaud) is working on a remake of Louis Feuillade’s Les Vampires (France, 1915) but he remains unhappy with the way the project is unfolding. Rene has cast Hong Kong action film heroine Maggie Cheung (Maggie Cheung) as the character Irma Vep and he has become obsessed with capturing the perfect take of her prowling the corridors of a gothic mansion in her latex catsuit. With the shoot running behind schedule, stress takes its toll and Rene suffers a mental breakdown. Alas, he isn’t the only person being affected by the strange intensity of his filming methods: Cheung has taken to donning her Irma Vep outfit and prowling the corridors of her Parisian hotel late at night.

Critique:

Following the same career arc that was enjoyed by many of the original French New Wave directors, Irma Vep’s writer-director Olivier Assayas wrote for the journal Cahiers du Cinema before making the jump to feature film directing in 1986. And, like a number of French film directors before him, Assayas went on to develop a special relationship with one of his leading ladies: he was married to Irma Vep’s star Maggie Cheung in 1998.

As such, it’s perhaps not too surprising to discover that some sections of this bitingly satirical film about French filmmaking appear to be mini-discourses that are specifically concerned with critiquing aspects of French cinema culture itself.

Rene Vidal is supposed to be an aging French New Wave film director. Cast as an all powerful auteur figure, nobody has the guts to tell him that he may have misjudged his decision to remake Les Vampires. Enigmatic and pretentious in equal measure, Rene is prone to using elaborate metaphors when he tries to communicate his needs and ideas to his cast and crew. They don’t have a clue what he’s talking about much of the time so they simply smile and sycophantically nod their heads in affirmation whenever he speaks to them.

Having seen Maggie Cheung in Johnny To’s The Heroic Trio (Hong Kong, 1993), Rene has seemingly developed a fetishistic need to film Cheung performing the role of Irma Vep. His apparent inability to grasp that Cheung’s most physically impressive scenes in To’s film were produced via a mixture of special effects and stunt work seems to be a comment on French art cinema’s traditional reliance on naturalistic working methods.

Jean-Pierre Leaud (who started his career as the young leading actor in Francois Truffaut’s 1959 film The 400 Blows) is well cast as the eccentric director and he communicates feelings of artistic failure and frustration perfectly when Rene hosts a tense screening of the film’s rushes.

There’s good work from the film’s female lead, too. Maggie Cheung is really quite delightful as herself. A non-French speaker, she looks genuinely lost and culturally adrift when she finds herself caught in the middle of French-only conversations but she works hard at remaining affable and happy in the company of her hosts. Most of them do speak some English, which results in the show featuring a lively mix of subtitled French dialogue and heavily accented English dialogue.

Maggie falls in love with her skintight latex costume and takes to roaming around her hotel’s corridors in it late at night, Irma Vep-style. At one point she sneaks into an American woman’s (Arsinee Khanjian) room and voyeuristically watches her taking a telephone call in the nude before making off with a discarded necklace. Next she prowls the hotel’s rooftop in the pouring rain. These scenes suggest that, just like Rene in the film, Assayas in real life could have easily lost himself in the act of shooting take after take of Cheung in her Irma Vep outfit.

The costume itself actually presents an excuse for some cinema-related discourse: Rene’s costume designer Zoe (Nathalie Richard) and Maggie trash Hollywood’s Batman films before realizing that Rene’s initial conceptual design for the catsuit was obviously inspired by Catwoman’s outfit. Zoe is a likeable but slightly unstable character and she takes it upon herself to serve as an unofficial personal assistant to Maggie. When she develops a crush on the actress some really interesting and well acted scenarios are played out.

Assayas alternates between a number of different but highly effective shooting and editing styles here. The film’s most striking sequences involve Assayas’ repeated use of long, roaming single-take shots that smoothly work around and briefly focus on a succession of expertly choreographed characters who are going about their day to day business. The film opens with one such shot that weaves around Rene’s chaotic production office, observing a number of key personnel whose conversations give some insight into the complicated business side of filmmaking in France.

Later on, a similar single take shot is put to good use when Rene’s film crew are observed hurriedly leaving a film lab and taking off in their respective vehicles. As the camera deftly pans and probes, the car park grows progressively emptier until we’re suddenly confronted with a disorientated Maggie, who has belatedly emerged from the building’s entrance and realized that she has been left stranded. Unsure of the way back to her hotel, it looks as though Maggie is set to become hopelessly lost until Zoe comes to her rescue and takes her to a dinner party.

A number of sequences in the film have an improvised quality about them and Assayas also slips in some documentary-like scenes that appear to feature non-professional actors (see the scenes where Maggie interacts with her hotel’s staff for good examples of this). The film also sports plenty of location work in environments that regularly appear in French art house films (cafe bars, the metro underground and so on). Most of the music used here appears to be sourced from pre-existing rock and pop songs but it works pretty well.

Another interesting aspect of the film is the variety of filmic textures that Assayas is able to employ. Well-worn clips from Feuillade’s original Les Vampires are used to remind us of the silent film era aesthetic that Rene is striving to reproduce with his remake. We can compare the two when Rene’s rushes are shown during a group screening at a film lab.

Assayas also presents shots from Johnny To’s The Heroic Trio, which are seen in a rather fuzzy video form shot directly from Rene’s television screen. At the dinner party Zoe takes Maggie to, one of Chris Marker’s black and white Groupe Medvedkine political films is shown playing on a television screen too. The inclusion of the Marker clips sparks another onscreen debate about another chapter in France’s filmmaking history.

Later in the film, Maggie is seen being interviewed on the set of Rene’s film and her responses are initially played to us via her interviewer’s video camera monitor. Another onscreen debate about French film ensues when the interviewer privileges Jackie Chan’s, John Woo’s and Arnold Schwarzenegger’s movies over French art house films and criticizes French art house directors for using state funds to make elitist films that only play to a small minority of citizens.

With Rene out of the picture, an old friend and fellow director who has fallen on hard times, Jose Murano (Lou Castel), is called upon to salvage the film. Unable to understand why Rene would cast a foreign actress as Irma Vep, the show ends with a somewhat surprised Jose viewing the crazed montage of manipulated shots that Rene managed to edit together before leaving the project.

Irma Vep is a fairly unusual film. It projects a generally fun and light-hearted ambience for much of its running time. But it also possesses the power to wrong foot and disorientate the viewer thanks to the clever way in which Assayas employs a real life actress to play herself onscreen. Maggie Cheung’s involvement here partially collapses the cinematic wall that traditionally stands between our own exterior sense of reality and the film’s own interior/diegetic representation of reality and the effect is really quite startling at times.

That exercise in itself perhaps indicates that Irma Vep is really just as knowing and just as arty as the films and filmmakers that it seemingly seeks to critique and satirize. I guess the big difference is that Irma Vep remains an accessible film that will appeal to both Maggie Cheung/popular cinema fans and art house cinema buffs alike. And it seems that that is the essence of the cinematic argument that Assayas has entered into here: just because a director sets out to make a film that is artistically worthy, it doesn’t necessarily follow that the film has to be inaccessible to the public at large.

Psychotronic Cinemas rating: Good ++

© Copyright 2008, 2016 Lee Broughton.

HOME | REVIEWS: A-Z | FURTHER READING | NEWS | ABOUT

You must be logged in to post a comment.